Pt 4 - David Tennant's Obscure Performances: The Incredible Story of 'Only Human' (2002)

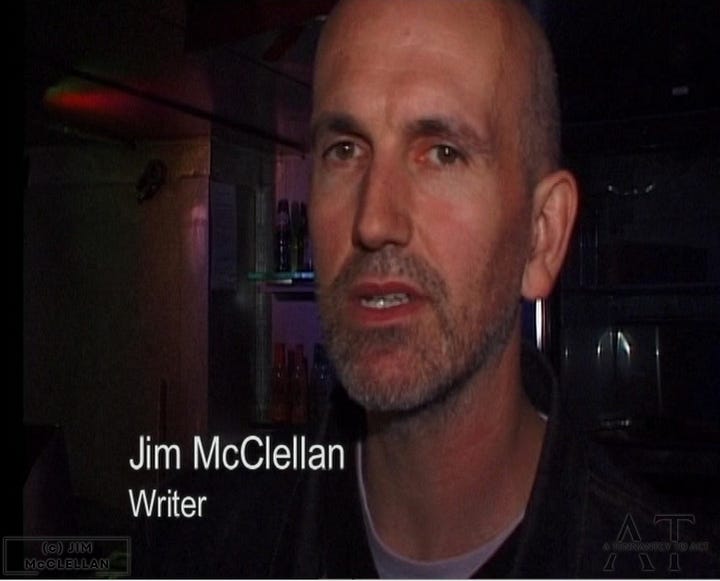

BBC Scotland doesn't pick it up, and Jim McClellan reflects on the many reasons why...

This is the fourth part of a five-part series about Only Human, an unaired BBC pilot made in 2002 and starring David Tennant as Tyler, a private detective who works with a virtual digital assistant called Ada. In this series of posts we’ll be exploring the origins of the pilot and unveiling its hidden history. Stay tuned for the rest of the series!

Make sure to read Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3 of the story behind Only Human before reading further.

…and be sure to watch the (first) pilot!

CLICK HERE TO WATCH ONLY HUMAN ON DAILYMOTION

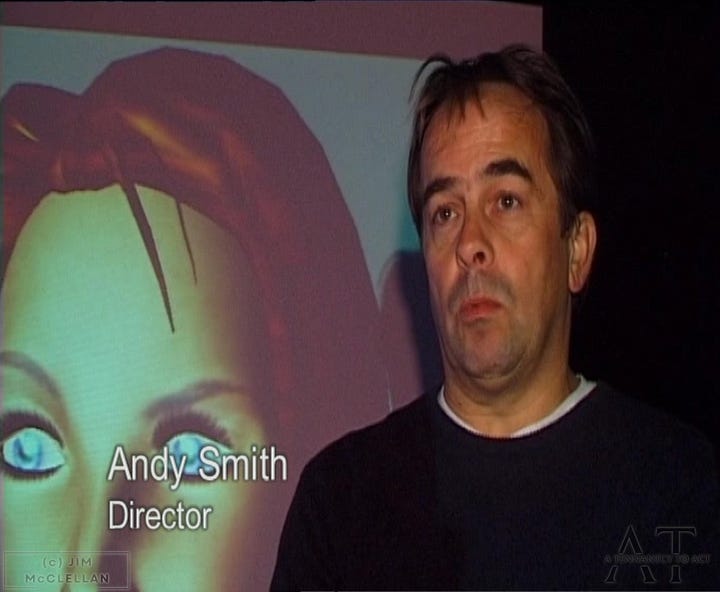

When we left our story last time it was early 2003, and Jim McClellan, Andy Smith and their team had wrapped the second shoot of Only Human and its second documentary, Making Of…Only Human 2. They had held a number of meetings with the brass at BBC Scotland about the second almost-pilot, continued to develop a script for an hour-long pilot episode, and made arrangements to send a DVD of both the pilot and its accompanying documentary to David (as well as the rest of its cast and crew).

David continued to fill his schedule with work. In November 2002 he did his third one-night-only staged reading for the Shakespeare’s Globe’s Read Not Dead project, John Marston’s The Insatiate Countess. A few months later on 23 March 2003, he joined many artists from theatre, opera, ballet, music and comedy for the charity Concert for Peace at the Theatre Royal in London.

In July, David revisited a version of Sophocles’ Antigone onstage for the first time since performing it with the 7:84 in 1992 when he played Haemon for Mendelssohn's Antigone in Prom 8 at the Royal Albert Hall (with Richard Hickox conducting the City of London Sinfonia and the BBC Singers). He spent the rest of the spring and summer of 2003 filming the short film Traffic Warden and episodes of Posh Nosh, Trust, Spine Chillers, and Terri McIntyre for television.

Meanwhile, everyone waited for BBC Scotland to make its final decision. McClellan said there was a long period where they didn’t hear anything - positive or negative - regarding the project. In the interim, McClellan and Smith continued to work on developing their hour-long episode script and hoped the decision-makers would agree to move forward with development for a proper pilot.

But ultimately, they didn’t. In the fall of 2003, BBC Scotland rendered its decision: they decided to pass on Only Human.

“BBC Scotland didn’t really say that much at the time about why they didn’t pick the project up,” McClellan told me. “When they did, the main problem they raised was how they couldn’t see the Tyler character as he was set up in the pilot, as a private detective - and more specifically, they weren’t sure about a private detective-led drama. Of course the idea always was that Tyler was a slightly odd kind of private detective, that he didn’t quite fit - but I think they just didn’t find it credible.”

Afterwards, the second shoot and all its related materials were packaged up on discs, and filed away.

This time around, though, the project didn’t sit stagnant for long. “Fairly soon after BBC Scotland passed, we had meetings at the end of 2003 with another BBC producer who had lots of sitcom experience,” McClellan told me. “He liked the idea of the relationship between Tyler and Ada and thought it might work as a shorter, half hour sitcom thing with a focus on romantic relationships. I think we had a meeting, and did some work around changing the focus of the idea. But it wasn’t really a surprise to find out once he had the chance to think about it, they didn’t pick it up. With all the motion capture, it was probably always going to be too expensive to do as a sitcom.”

Once again, the project ground to a screeching halt - and this time, it sat for well over two years. McClellan and Smith had both decided to move on from BBC Imagineering (by this time renamed to Creative R&D) and enter academia; McClellan as a senior lecturer in Journalism at the University for the Creative Arts in Farnham, and Smith in film and TV production.

“We’d put the project to one side,” McClellan said. “But then another guy got in touch with Andy and said he was interested. Again, nothing ever came of it in the end. I think his interest was connected to the fact that David might still be attached to the project.”

He wasn’t - but it was understandable to consider whether he was or not. By that time, David’s profile had raised quite a bit. You see, he was a bit busy beginning his journey in a little show called Doctor Who.

—

Before we move on and talk more about Only Human’s inevitable end, I had to ask McClellan one of my own burning questions: does anything of Only Human other than the pilots and documentaries still exist in anything but photographic form?

“Oh, sure,” he said. “We were doing development work with BBC Scotland. There's a pile of other stuff which is not on the internet.”

He told me both pilots - first and second - exist in their entirety on video footage, as do both Making Of…Only Human documentaries. And there are B-rolls, too!

“The B-roll footage comprises alternative takes that weren’t used and also incidental stuff we could use for edits and cutaways,” McClellan explained. “There’s footage of David goofing around in Tyler’s flat, and street scenes in Docklands. There’s also some footage shot around London, as we’d asked a young director to shoot around the city but try to make it look vaguely futuristic. I guess the idea was to see if we could capture this kind of ‘five minutes into the future’ feeling that was part of Only Human. You know, the idea that it was happening in a world that looked like the present, but was also subtly different…in other words, not a bright, shiny stereotypical futuristic world.”

—

McClellan always thought he’d come back to Only Human at some point in his career, but in the end, he never did - life happened, he shifted into the academic world, and time marched on. He said that until I’d approached him and asked, he hadn’t given the project much thought for some time.

My months of conversations with him have seen him widen his perspective a bit on Only Human’s final act, now that he’s had ample time to find, re-watch, re-read, and revisit all the remnants (pilots, documentaries, scripts and story development work) he still has from it in his possession. I’ve noticed more of his long-buried memories come back to him as time’s gone on…and along with them, more opportunity for reflection. At the time he says he was disappointed it hadn’t been picked up, but he was too busy to worry about it overmuch; as an Interactive Writer in Residence sponsored by BBC Creative R&D, he had a number of new projects on the go.

McClellan believes one of the factors in the decision was probably financial; because of the show’s heavy dependency on technology and how expensive it would be to produce, there was more risk involved for partners if it wasn’t a successful show. “It was tricky for BBC Scotland,” he said. “They were justifiably nervous, because with all the technology, it was going to be expensive. I think they needed to feel sure it was going to be a hit.”

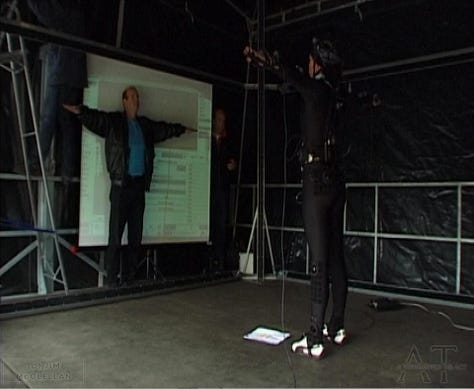

The collective focus on technology over story seemed quite sensible at the time, and each of the key players had their reasons for its emphasis. BBC Imagineering - who was focused on bringing new tech into traditional TV production by building relationships between computer experts and TV production technicians - felt Only Human could be a showcase for such innovation. And BBC Scotland, of course, had fronted the majority of the development money and wanted to see a return on their investment.

But McClellan also believes financial factors probably weren't the sole (and maybe not even the main) reasons why BBC Scotland decided not to pick up Only Human. In the end, he said, the key thing was that the pilot script didn’t convince BBC Scotland the idea could work as an extended drama series with hour long episodes. Twenty years on, he says, he’s not as close to it as he was at the time, making it easier for him to identify a few things he might have (or should have) done differently.

McClellan suspects his revised script might have had something to do with the reason BBC Scotland didn’t find Tyler’s character development convincing. While the initial pilot portrayed him as a private detective without much back story, the revised script depicted him as a likeable, but aimless and drifting sort of guy. BBC Scotland found this implausible as a detective origin story. “[They] didn’t find it convincing that [Tyler] would end up being a private detective. The oddness of this idea was intended as one source of the comedy, and over time, we would have learned Tyler had hidden depths and a past he was running from. But, like I said, BBC Scotland just didn’t feel able to go with that.

“I think BBC Scotland didn’t buy all of the comic elements in the pilot script - not all of which worked,” he admits. “When you’ve got brilliant actors like David and Ruth, they can find the funny side of the lines. But sometimes, it’s hard to see that on the page, especially if you’re starting to be a little unconvinced by the main character.”

McClellan also wonders whether the script may have been overly quirky. “Although the central premise is a very science fiction-y one, I tried to move the stories in the direction of comic misunderstandings, human dramas and relationship dilemmas. I probably went a bit too far in that direction. It might have worked better to have more big science fiction set pieces and plot twists and tropes.”

It also didn’t help that the script offered more in the way of world-building than it did page-turning, high-octane drama, and McClellan feels making the stakes a bit higher would’ve been a better choice. The script also fell a little flat and didn’t develop the female characters, despite their intended importance in larger story arcs. “It sets up the world and plants things that will develop into big story lines later, but perhaps there was too much of that,” McClellan said. “Sally was going to be a really important person in a larger series. I could have hinted more at that and [teased some] more detail about her character.”

In retrospect, McClellan said he also thinks his enthusiasm ended up cluttering the narrative. “I was always seeing possible new dimensions to the central idea (the relationship between a man and a - possibly intelligent - machine) and kept adding strands to the story (around the way tech might develop, AI, intimate tech, ubiquitous networks, surveillance, data gathering, stats and attempts to nudge, predict and control what people do). I think it might have been better to focus the pilot more, and just leave some things hanging or unexplained.”

Another concern McClellan mentioned BBC Scotland may have been responding to was how Only Human would fit into the programming of the time. The urban, sci-fi style of Only Human was quite a departure from BBC Scotland's typical programming, which often focused on present-day or period dramas primarily set in rural areas. What’s more, the private detective genre itself had started to lose its luster with the viewing public, as crime shows featuring police took precedence over those centered around private investigators. The fact Only Human bucked all these trends may have given BBC Scotland pause.

He also mulls over whether they would have been less worried if a few big-name, experienced actors and show runners had been associated with the project. But Only Human didn’t have that. David and Ruth were up and coming, Smith had a track record in sitcoms but not drama, and McClellan himself had written a lot on the net and done some comedy stuff about technology. BBC Scotland's reluctance to proceed may have in part been rooted in their nervousness over investing in an untested and unconventional venture.

But McClellan is quick to say he’s theorizing, because BBC Scotland didn’t say any of this to him or Smith at the time. “They didn’t talk about the issues I identified in the script, and they never talked about the high cost of the tech. That’s me, speculating. Though I think it’s a safe bet they were worried about the cost of all the tech, and the fact it was money they’d be spending on people who didn’t have a big track record.”

Then there’s the second shoot.

“In a strange way, I don’t think the second shoot helped us,” he told me. “In fact, looking back, it slightly undermined the idea - though that wasn’t anyone’s intention going in, and it was done with the best of intentions.”

What he means is that, despite being plugged by BBC Imagineering as a test of whether motion capture tech could be used on location to create a believable virtual character who could interact in real time with a real actor, the first pilot ended up being more than the sum of its parts.

“David and Ruth had enough to work with in terms of the script to create characters you went with - and scenes that were silly but also funny and dynamic,” McClellan explained. “In terms of direction, Andy managed a really nice mix of comedy with a darker, noir-ish visual aesthetic. The whole thing has a kind of fun energy - it’s certainly a long way from perfect, but you go with it.”

In other words, it turned out people enjoyed the first pilot for its engaging narrative and comedic elements, rather than only for its technology. There were some technical issues, sure, but they liked Ada and Tyler and could see potential in the relationship. The way forward seemed clear - all they needed to do for the second shoot was to deliver more reliable, robust motion capture technologies.

And that’s what they did.

McClellan says this approach suited Imagineering/Creative R&D — which was always more focused on tech and less on stories and ideas. “As a department, it was about creating interesting demos that helped traditional TV creatives and production people think about using new tech,” he explained. “Also, because everyone thought the story, characters and general idea worked in the first pilot, we focused less on that. We decided to reshoot some old scenes, do only one longer new scene, and tried three different actresses in the Ada role.”

McClellan says these choices led to a host of problems. “First of all, though technically the new versions of the scenes are better, they don’t have the feel, the energy or the fun of the first pilot. They feel a bit familiar, like something you saw before but it’s not as good now as that first time. I think the new actresses faced real problems, too - they didn’t have as much script to work with as Ruth, and didn’t have as much time to build their own interpretation of the character. They also had a lot more tech to deal with.

“The new tech led us to try things that were also, in hindsight, a bit beside the point,” he continues. “Like the work with more complicated gestures. Because we were able to do it in the set up with Ivana in the re-shot bar scene, there’s perhaps too much of it. In the end, what a project like Her showed is that you don’t need to see a ‘realistic’ virtual character. Sometimes less is more.”

In hindsight, McClellan feels, it would have been better to create a new and shorter episode with a stable tech setup, rather than rehashing old scenes. “I think the new scene - with Tyler, Sally and Ada - does work. But in retrospect, it would have been better to do a short six- to eight-minute episode, completely new, telling a little story, featuring the three characters, in three or four new scenes (including the drinks scene we did) and with one new actress doing Ada.

“All this was exacerbated by the fact that the key thing we got from the second shoot was the second Making Of… documentary, [which] starts and ends with a focus on tech,” he continues. “It opens with the issues we faced on the first pilot, has a lot of detail about the new set up, and ends with Andy [Smith], Rowena [Goldman] and Quentin [Plant] talking about how the tech problems have been solved and the second shoot has brought traditional TV people and computer techs together.”

The result of the second shoot, McClellan feels, was the exact opposite of the first pilot - the tech was an achievement, but it overshadowed the narrative. Ultimately, there was a disconnect between the technical success of the second shoot and the underwhelming storytelling compared to the first pilot.

“This is speculation on my part, but I can imagine people from BBC Scotland looking at this and thinking, this clearly works for BBC Imagineering/Creative R&D’s mission and brief, but what is there for us, as a drama department? Do we believe enough in the idea to pay for all this tech? And I guess the second shoot didn’t give them anything new to look at in that respect beyond the one new scene, and it had slightly less effective versions of scenes they’d seen before working better. So, they went back to the draft script for the long pilot perhaps a bit less into the idea than before.

Plus, McClellan says, “I was inexperienced and a little overwhelmed, and we were a little bit out of our comfort zone. You get drawn into all that, when the real thing to focus on is just to make sure the first episode works. Looking back,” he adds, “I think maybe if BBC Scotland had paired me with a more experienced writer and also paired Andy with a more experienced drama director or something, it might have worked a bit better.”

If McClellan is right, Only Human’s flip-flopping from story without tech to tech without story backfired with the very people it was trying to court. It closed the chapter on Only Human for good.

But we’re not quite ready to close it for you, dear readers.

Not just yet.

Because, you see - while the television show may have saddled up and ridden off into the sunset - because of Jim McClellan, there’s still an astonishing amount of the world of Only Human left for us to investigate.

I think he put it best: “People unexpectedly liked the idea, so I thought, right, what do I have to do? I started watching loads of early prestige TV (like The Sopranos and Six Feet Under), when people were beginning to see how extended drama on TV could get into really interesting, complex areas. I thought maybe I needed to map out series arcs, and have a massive bible of characters, and think about where it might go in Series Two and Series Three.”

Next time, in our closing chapter on Only Human?

We’ll go there, too.

—

‘Only Human’ images courtesy of Jim McClellan (c) 2024. A Tennantcy To Act/Patricia Browning. All rights reserved.

Thinking about this pilot and project in its original time period, I can understand how a corporate entity would have been reluctant to pull the trigger on an innovative concept like Only Human. Technology evolved so rapidly, once it got going, that the learning curve would never have ended for a production based on leading edge technology. But I would still like to see everything that was recorded and saved! Thank you for your ongoing in-depth investigation into this fascinating time of groundbreaking innovation.

It seems like they were breaking new ground and on the cusp of a new idea that is now so common. It's too bad it wasn't expanded as it could have been one the trailblazers of the computer/person relationship and slice of life films that permeate our streaming feeds these days. Keep it up.