Early Theatre Deep Dive: David Tennant in 'The Ghost Of Benjy O'Neil', Pt. 1 (1989)

...we finally get around to one of David's most well-known early plays!

Before we begin: a personal note. Thanks to all my readers for your patience over the last month and a half as I recovered from my super scary bout with sepsis. I’m feeling loads better and I’m stupid excited to be able to return to writing…which of course means sharing everything David! Now, on with the show!

-

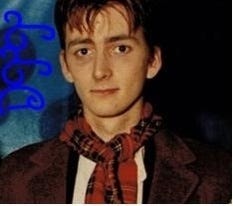

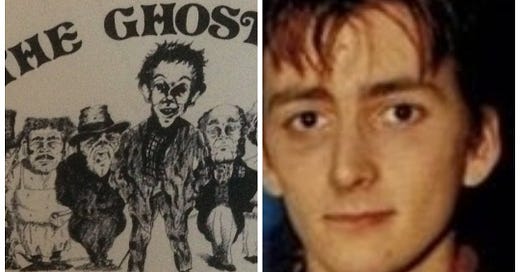

If you’ve been a fan of David Tennant’s for any length of time, you’ve probably heard of The Ghost Of Benjy O’Neil. It’s earned legendary status in the DT fandom. This may be because it is the first stage play mentioned on David’s list of performances Wikipedia page, or because a few pictures of him in the lead role of Benjy O’Neil (as well as a few pictures of him in rehearsals for the play) have been in circulation for years around the Internet. I’m not exactly sure.

But I have to admit…I’ve always been a wee bit obsessed with it, too. When I became a fan of David’s almost fifteen years ago now, it was one of the first pieces of work I was eager to learn more about.

In those days, the way you learned about early David stuff was to go to a website created by Diane Medas called The Play’s The Thing. I’ve mentioned The Play’s The Thing before, but it’s worth another mention. The website had a section about The Ghost of Benjy O'Neil and an interview with Tommy Crocket, one of its authors. It was my first exposure to this glorious piece of David’s early catalogue. I’m sorry to say the site went dark in 2016, so in order to catch glimpses of it, you’ll have to use the Wayback Machine.

Fast forward to 2017. I’d been keeping an eye out for mentions of The Ghost Of Benjy O’Neil and ran across something spectacular on Twitter - a photo of David in rehearsals for the play, tweeted out by one of the other cast members in the photo! I immediately reached out to the poster, Terry Forey. He was delightful, and was happy to chat with me about his memories of the production.

He also told me two incredible things:

he’d get me in touch with the play’s author, Tommy Crocket, and

The Ghost Of Benjy O’Neil had been recorded! And he knew how to get me a copy.

To say I was gobsmacked was an understatement. You mean I get to talk with Tommy Crocket, the author of the play? (Yes, you do!) And wait, what? You mean to tell me that The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil was actually recorded on video? (Yes, it was!) And I could have a copy? (Yes, I could!)

And yes, I eventually got a copy. And oh, my, my. Believe me…it is fabulous!

From that day to this, I’ve learned so much more about this production. That in itself is a triumph, since many - if not most - of the plays David did during this early time period suffer from a profound lack of information. But I know more about this one than I know about any other early play David’s done. So, there’s an amazing story to be told here, and it’s a huge treat for me to be able to share it.

It’s way past time I tell you the story of The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil.

-

The tale I’m about to tell of this pivotal early play is a lengthy one, and there’s no way I can share it in just one post. I’ll have to tell it in multiple parts and with significant detail to do it justice. I hope I’ll be able to give my readers - i.e., those of us on the outside - a unique glimpse into that time and what was happening around David and everyone else on the production. I aim to make it feel like we were there, too.

But oh, yes, a couple more things before we get started.

One - I’ll be talking a lot about Strathclyde in this series of posts, so the term needs some explanation. Strathclyde was one of the nine local government regions of Scotland between 1975 and 1996. It was made up of nineteen districts and had an administrative headquarters in Glasgow. You can see all of its regions in the map below. Strathclyde existed as a region until 1996, when it was abolished.

Two - I’ll be referring to a number of people who have graciously contributed their time and memories to help me reconstruct the story of The Ghost Of Benjy O’Neil. A few didn’t want their names mentioned, so in keeping with their wishes, they’ll remain anonymous. Others I can thank include production cast members Terry Forey and Christine (Gibson) Urquhart, and the play’s (now-deceased) author Tommy Crocket. I also owe a huge debt of gratitude to the play’s Production Coordinator (and largest contributor of information for this series of posts), Robert McAteer. Robert’s remarkable memories have given me an embarrassment of riches!

Three - I’ve already written an article about one part of this saga: the fact a scene from the play was performed in front of Queen Elizabeth II! I did a detailed introduction to the play in that post:

…and I’ll be pulling parts from it shamelessly for this one. So, if you’ve read both and find yourself sure you’ve heard some of this before…it’s because you have!

-

What eventually became The Ghost Of Benjy O’Neil all started in late 1988 with the Strathclyde Regional Council’s Department of Social Work. Glasgow had been named 1990’s European City of Culture (renamed the European Capital of Culture in 1999), and it planned to become the first to provide a 12-month programme of activities.

The city also wanted to place a heavier emphasis on improving access to cultural activities for under-resourced or traditionally marginalized social groups. To that end, the Strathclyde Regional Council asked its Social Work staff to begin brainstorming ideas for anything and everything artsy and creative.

Well…sort of.

Actually, they asked Robert McAteer.

“I got a phone call from my manager asking me to submit a funding proposal for a project to mark Glasgow being awarded the status of European City of Culture for 1990,” McAteer told me. “When I asked when the proposal was needed? ‘4 o'clock today!’ came the retort. No pressure then!”

McAteer, who worked for the Department of Social Work and had studied social history at university, had a particular interest in how the provision of child care to the most needy had happened over the centuries. He decided to put his interest to good use and compiled a bid outline for a series of ten lectures. He planned for these lectures to highlight the changes in support and attitudes to the poor over a two century period.

“The initial plan was for me to write the script, and a young care leaver I’d worked with would deliver the monologue,” he explained. “This young man was into amateur dramatics and would’ve been a natural! I submitted the bid, and boom...£300 awarded to cover basic traveling costs (as well as a bit of a financial ‘bung’ to my young thespian). But once I started researching, I changed direction and decided audiences needed to be part of this social history. I thought through the narrative of a script in conjunction with dance and song, the story would be better told in a theatre!”

As soon as McAteer determined this was the way to go forward, it didn’t take him long to picture the developing project as a musical play showcasing child care provision changes in the West of Scotland. He also had a pretty good idea about who’d be best equipped to write the script: his long-time friend and colleague, Tommy Crocket.

McAteer and Crocket went way back: they’d went to the same senior school, lived in neighboring communities, and became friends during the 60s before going their separate ways. Their paths crossed again years later when both men started working in an assessment centre for troubled young people - McAteer on the social work side of its operations, and Crocket and his friend Gordon Wilson (a talented artist, musician and songwriter) in its education unit. All three men were dedicated to helping young people in care.

But Crocket wasn’t just McAteer’s long time friend: he also had credentials. He was a creative writer. Alongside Wilson, Crocket had written screenplays and sketches for a topical gag comedy sketch show out of BBC Radio Scotland called Naked Radio (as well as its sister television show, Naked Video) and for a sitcom series called City Lights. So McAteer was confident Crocket had the know-how to complete a script.

Crocket was teaching at the Residential Child Resource Centre in Cardross when McAteer approached him about whether he’d be interested in writing the play he had in mind. Crocket most certainly was, but he had one request - he wanted to bring in Gordon Wilson, too. Crocket was certain Wilson had the musical chops to incorporate the song they wanted into the production.

McAteer agreed, and Crocket and Wilson immediately went to work. It didn’t take long, however, for the pair to realize they would need time away from their everyday duties in the Strathclyde Social Work department to deliver the script.

McAteer pleaded their case for weeks before he finally managed to secure the two men a ten-week secondment. He played it safe, though, and factored in a bit of a buffer in case they didn’t meet the deadline date: he told Crocket and Wilson he could only get them six weeks away!

McAteer set Crocket and Wilson up in an empty office in a home for the elderly in Maryhill’s Burnbank Gardens…not that they used the office much! A mere ten-minute walk away from the office was an iconic Byres Road pub situated next door to the Hillhead subway station which at that time was called The Curlers.

It’s called Curler’s Rest now, and it’s still there.

Anyway, I’ve got it on good authority that the lion’s share of the script for The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil was written in that pub. So if you’re ever in Glasgow, go on in, have a seat, and raise a pint to a part of David Tennant history!

Crocket and Wilson delivered the script and its musical interludes with time to spare and exactly as detailed in the funding application for the project: “To present a historical perspective of child care provision from the enactment of the Poor Law (1834) to date.”

McAteer looked the finished script over and was immediately impressed. Crocket had run with the idea and crafted a compelling narrative framework by using a boy’s ghost as a transitional conduit spanning the centuries of child care changes in Scotland. McAteer thought the script extremely creative and clever.

He only had a few suggestions. The first was pragmatic: tone down Crocket’s blistering criticisms of social work system management. Regardless of how he personally felt about the veracity of Crocket’s observations, McAteer knew management held the purse strings. Their additional funding would be needed to bring the production to the stage. Leave it as is, McAteer thought, and he’d risk losing the entire project. It took a bit of convincing, but eventually Crocket agreed to err on the side of pragmatism.

McAteer also made one more change...and this one was a big one: its title.

In the original script, the ghost wasn’t named Benjy O’Neil. Crocket and Wilson had chosen to call their main character Benny O'Neil. McAteer pointed out the O’Neil family was of Irish descent, and suggested an alternate name - Benjy. Crocket and Gordon readily agreed.

It was early 1989, and The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil was born!

—

It had always been McAteer’s intention to form the majority of the cast of The Ghost Of Benjy O’Neil from young people in the care of the Local Authority, whether they were actors or not. Others didn’t feel the same. Doubts quickly began to circulate about whether young people in care would have the discipline to make the project a meaningful experience.

But McAteer believed in the kids. He championed the belief that given opportunity, encouragement and support, young people in care could compete and achieve. He was worried that if he didn’t act, they’d end up getting unfairly pushed out of a production specifically written about and focused on their experiences! To prevent this, he insisted senior management needed to make the casting of young people in care a condition of the agreement when they went to the Council for further funding. They did, and eventually their funding was granted.

As the production’s Project Coordinator, McAteer’s plan was to arrange for a set of four performances in Reid Hall at Maryhill Community Central Hall (located at 304 Maryhill Road). He scheduled the performances for the first part of December 1989, which gave him eleven months to pull everything together.

Along with casting and organizing the production's staff and crew, securing funding was imperative. “Throughout the whole of 1989, every adult involved with The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil had volunteered their time,” McAteer said. But he also understood that depending on volunteer work wasn’t sustainable over the long term. To obtain the added funding he knew he’d need, he formed a production company called Phantom Productions to take advantage of a social work vacancy post and its additional funding. McAteer then had enough wiggle room to establish a budget and hire some professional staff.

The play’s authors Tommy Crocket and Gordon Wilson - who had already done such a fantastic job writing and scoring the play - were also ready and willing to remain intricately involved with the project. The two men participated throughout rehearsals, and worked with the young people for months. On the recommendation of Wilson’s partner Sandra (who, incidentally, helped write a chunk of the score), McAteer appointed recent RSAMD (now the Royal Conservatoire) graduate Mercedes McGurn as The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil’s director. Mercedes in turn brought on board a fellow recent RSAMD graduate, Eleanor Goodman, as co-director.

Then there was the matter of the cast.

“One of my responsibilities in my paid work was as External Manager to all the residential children's homes in the northwest of Glasgow,” McAteer told me. “There were seven of those in total, with a combined population of 120+ children and young people, mostly teenagers. Every one of them was a potential cast member. I was a known face to most of the young people, which helped me win over twenty or so to come volunteer for auditions.”

McAteer also had an additional resource which became very useful: there was already an established theatre company at Maryhill Community Central Hall called the Maryhill Youth Theatre company. While the five principals (McAteer, Crocket, Wilson, McGurn and Goodman) were committed to using young people in care, they were all relatively certain directors and crew couldn’t harness their raw talent in time to get them prepared for the shows without additional support. Maryhill Youth Theatre offered the fledgling production that support. A decision was therefore made to “merge our young cast with members of that theatre company,” McAteer said.

Preparations began. Adults from the NW Social Work department volunteered to contribute their time, and a few were even added to the play’s cast. Backstage crew and support staff were chosen, and auditions kicked off for each of the roles in the play. Crocket, Wilson and McAteer established a policy early on that any young person with a link to Social Work and who wanted to get involved was accommodated in some capacity. Members of the Maryhill Youth Theatre were tapped for a few roles, but the majority were given to the young people in care. Throughout the process, everything possible was done to consider the support their young cast would need as well as make the best choices for the production.

In addition, McAteer was also painfully aware of one other critical fact: the future of the show was all down to how successful their first four shows were. The Regional Council was open to the possibility of a tour of the play throughout the Strathclyde region, but only if the show performed well. If it didn’t, the play would open and close with those four performances.

The show had largely been cast by late March/early April 1989. When initial cast meetings started, however, it was immediately apparent to all five principals that they’d need to make some adjustments for the inexperience and anxiety of their young social work cast members. The vast majority of the young people had never been on stage before and were understandably apprehensive. Most struggled with self-doubt, and a few even became disruptive in their attempts to self-soothe.

Though these growing pains subsided as weeks passed (and the confidence of the youths in care grew and their natural abilities began to shine), those first few get-togethers made one thing painfully clear for everyone involved: the play was still lacking that special talent who could play the pivotal lead role of Benjy O’Neil.

Enter David Tennant!

“The directors [McGurn and Goodman] doubted any of the cast had the skills to carry off the role of the ghost in the play, and we simply didn’t have the time to allow for their development,” McAteer told me. “Their suggestion was to approach the Royal Scottish Academy for Music and Drama. If I recall correctly, I believe it was [McGurn] who had a contact within the Academy. The outcome of that was that David was recommended as a possible solution to our dilemma.”

According to the play’s author Tommy Crocket, David was friendly with McGurn. “[McGurn] had an aunt, Liz McGurn, who worked with the Northwest Social Work Department. I think it was Liz who suggested Mercedes fit the project well, and she in turn brought David in.”

Here’s how Robert McAteer described David’s arrival as Benjy:

My initial concern was that by bringing in an "outsider" we risked being viewed as compromising the underlying ethos of the project. These fears were quickly dispelled once I met with David. He was an extremely clever and likeable young man who just oozed talent. I watched him closely at the first rehearsal he participated in, and the way he interacted with the other cast members - in particular, those with a care background - was so impressive, I felt like offering him a job in a children's home!

David’s obvious talent not only raised the spirits of everyone connected with The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil, but also elevated the levels of performance and confidence of each and every other young cast member. His presence as the "head" of the show was a calming influence for some of the younger and more volatile members of the cast, and his kind, calm nature put the others at ease. He had an instinctive ability to quickly and quietly direct them away from disruptive behaviors.

Play author Tommy Crocket agreed. “David was a great inspiration to the young people. They loved him. He had no airs and graces, and got on with everyone.”

-

Next time, we’ll head into The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil’s rehearsal room…and be there when it makes its debut.

================================

One last thing. I want to speak briefly about Tommy Crocket.

Tommy and I “met” online in January 2018. Over the next four years, Tommy became a friend of mine. He gifted me a DVD copy of the recorded performance of The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil and provided me with a copy of the programme for the play as well as a number of photos and newspaper reports. When I moved to Glasgow in late 2018, we finally arranged an in-person meeting, where I attended a play with Tommy and his lovely wife Elspeth. Later they invited me to dinner, and I spent a fantastic day with them which I shall always remember with great fondness. Sadly, Tommy Crocket passed away on 18 April 2022 (yes, on David’s birthday). His obituary mentions his many achievements, including his involvement with The Ghost Of Benjy O’Neil. You should read it.

no wonder DT fans are passionate about this story; not only does it demonstrate that David has immense acting talent and the work ethic to have developed serious acting skills by the age of 18, it's also good evidence in favour of him being kind and compassionate, which is extremely hard for fans to be confident about with any celebrity, let alone actors. Thank you so much for sharing this story, both because it is very reassuring in terms of David's character, and because I found it (I've read all 3 of the installments available so far and am now leaving reactions) a very entertaining read 💜

how young he looks in that photo! 🥺 so glad you're feeling better ❤