Early Theatre Deep Dive: David Tennant in 'The Ghost Of Benjy O'Neil', Pt. 3 (1989)

...David Tennant sang his heart out in a gritty Glasgow musical—and yes, there's footage!

Before we begin this all-important Part 3 of the tale of The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil, I recommend you go back and read Parts 1 and 2 if you haven’t already (or to refresh your memory if you have). You can find links to both below - so go read and come on back:

—

When last we left the intrepid cast of The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil, they’d done a dress rehearsal where they fell flat on their faces…and they hadn’t taken it well. The cast was in shambles. Even David (who was suffering from a viral ailment and wasn’t feeling great) didn’t take it well.

But they had little time to indulge their insecurities. The show was opening to the public the next afternoon, so they had to suck it up and get on with it. They were scheduled for four shows in Reid Hall in Maryhill Community Central Halls - three evening shows and one matinee show, with tickets selling for £2 each.

Sat, 2 Dec 1989 - Maryhill Community Central Hall - 2:30p and 7:30p

Sun, 3 Dec 1989 - Maryhill Community Central Hall - 7:30p

Mon, 4 Dec 1989 - Maryhill Community Central Hall - 7:30p (filmed performance)

The cast knew the Monday show would be filmed, but Production Coordinator Robert ‘Rab’ McAteer had another curve ball he hadn’t thrown their way: the administrative brass of the Social Work Department, the Glasgow City Council, the Regional and District Councils, and a representative from the Scottish Office were scheduled to attend the Saturday night performance! He didn’t tell them about their visit at first because he was afraid it would send them over the edge as opening night approached. After the catastrophic dress rehearsal? He decided against telling them at all.

—

We’ll leave the terrified cast behind on the eve of their opening for a moment to take a closer look at everything surrounding them.

Firstly: the artwork.

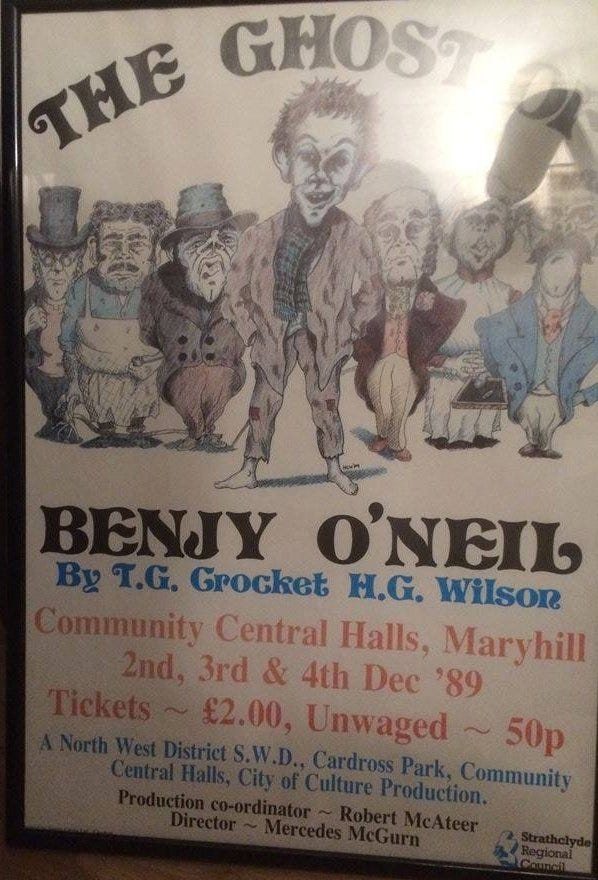

Gordon Wilson designed the art for Benjy’s production programmes and T-shirts, as well as the art which graced the front covers of VHS tapes given to the production members. I mentioned in my last post that Wilson had based his sketch of Benjy on a caricature he drew of McAteer; he used that image again for the show’s color promotional posters. McAteer’s rendering of Benjy took center stage on the poster, and the other caricatures Wilson added were based on other senior social work managers Wilson knew.

Secondly: the promotional materials.

In the run-up to their opening performance at the Maryhill Community Central Hall, T-shirts and posters were sold in the foyer.

The publicity posters for the initial performances didn’t look like the poster Crocket is holding in the photos above; instead, they featured the production’s promotional slogan - “Watch Out For the Ghost of Benjy O'Neil” - and almost certainly resembled the art on the T-shirts:

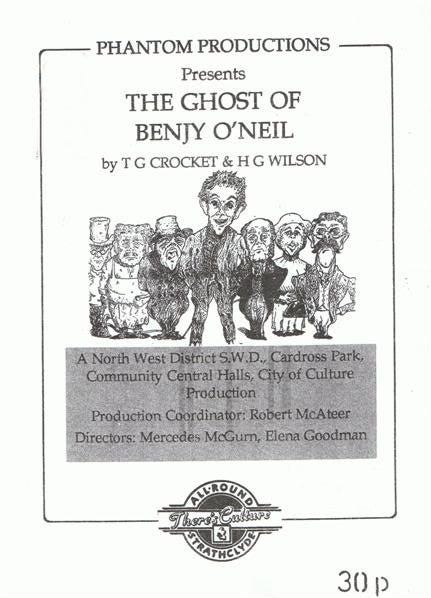

A printed programme was also created for the production. It included the now-familiar cover art by Gordon Wilson, an introduction to the play by Production Coordinator Robert McAteer, and full lists of cast members and production team members.

Lyrics to each of the songs sung in the play were also included in the programme, and it was made available for sale to show goers for the sum of 30p.

—

We return to the cast of The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil as they began preparations for their first public performance—the 2:30 pm Saturday matinee on 2 Dec 1989. The dress rehearsal disaster of the night before was still painfully fresh in their thoughts. Spirits were low as they arrived at Maryhill Community Central Hall for early morning rehearsals.

Tommy Crocket and Gordon Wilson were waiting for them. Both were trained social work professionals as well as talented creatives, and brought all their teaching skills and training to bear. With their help (and the fact David was beginning to get over the virus he’d had), the Saturday matinee went well, and the audience seemed to enjoy the play. The warm reception put smiles on everyone’s faces and went a long way to easing the sting of the night before.

The young cast carried the feeling of that success straight into the 7:30 pm performance later that evening, because they made a spectacular comeback: the main event was a roaring success!

It was a good thing it was, too, for not only were the families of the company in attendance, so were all the dignitaries McAteer had neglected to tell them about for fear it would paralyze them with stage fright. But the cast were firing on all cylinders, and at the close of the show, the audience gave the young actors a standing ovation. And the dignitaries? Well, they were pleased as punch.

Something else pretty remarkable happened. “Apart from the matinee, all their other shows were sold out,” McAteer said. “Indeed, by the Monday [the evening the show was filmed], news had spread about the uniqueness of this 'bold experiment'. It was standing room only.”

It was standing room only!

-

And now—drumroll, please—this is the part you’ve been waiting for! It’s time for your front-row seat to the show.

It’s curtain up. Onward, then, to the play!

Please note: The following screenshots, audio and video clips were sourced from digital files created by converting an original VHS tape recorded on 4 December 1989. As a result, quality may vary due to the age and condition of the original material.

Time has left its mark, so expect a bit of blur, fuzz and flicker along the way!

In this section I’ll be your guide through the filmed recording of the play. In stories, in screenshots and in video clips, I’ll do my best to tell you the story of The Ghost Of Benjy O’Neil!

This play uses an ingenious framework: dragging the audience back and forth in time. Of course we all know that’s one of the fundamental principles of Doctor Who, but it’s really cool that it pops up here, too, long before he got the chance to play his beloved Doctor.

When the play opens, a bell is ringing. We are in the present day at Hagburn Day Centre, watching a social worker teaching a class of young kids in care.

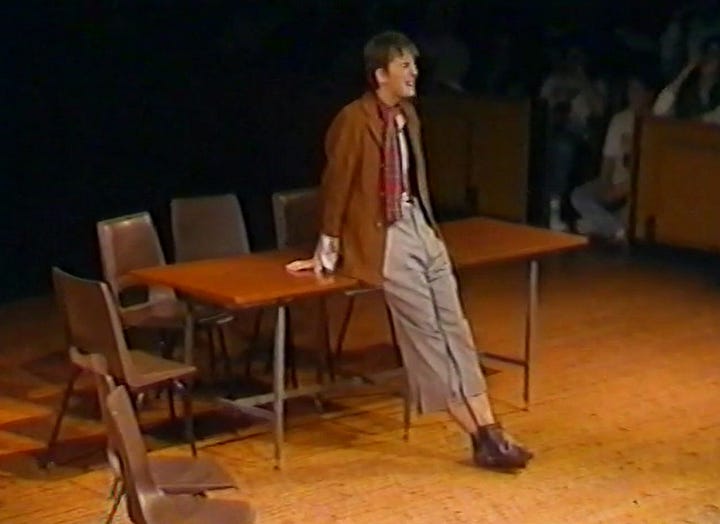

As they go about their school day, a tall young man walks in from stage right. His old, mismatched clothes hang awkwardly on him, and look like they’ve been pulled out of a thrift store time machine. He paces slowly around the periphery of the room before settling himself at the edge of the scene. His skin is ghostly pale. No one so much as glances his way.

The pale young man is clearly surprised as he watches how the kids speak to their teacher. But when one of the kids mentions their father went to jail for stealing, Benjy can’t stay quiet anymore.

As he begins to speak, the day centre kids and their teacher freeze in place.

“That’s what happened to my da’, gone to jail for stealin’,” the pale young man tells the audience. “Over a hundred years ago. I’m deid now, but I was glad at the time, though. See these weans today…what a great time they have. See how they spoke to the teacher? I’d have been murdered for that!”

The scene changes, and we find ourselves in 1870 (via the device of a chalkboard at the back of the stage, which is used throughout the play to note locations and dates - you can just spot it in the scene above to the far left behind Benjy.)

We learn the pale young man is Benjy O'Neil, an Irish boy whose family fell on hard times and eventually found themselves in the Barnhill Poorhouse—once located on the very grounds where the Hagburn Day Centre now stands.

Benjy begins to share his story. He recalls how he and his family were living in cramped quarters, out of work, and desperately poor. He introduces us to his mother Mary, his brother Patrick, and his sister Margaret.

Benjy’s father had lost his job. With no work and no way to feed his children, Benjy’s father made a desperate choice and turned to stealing to feed his family. When he was caught, he was sentenced to seven years behind bars. The O’Neil’s - who were living in a rundown hovel in the Briggait near Glasgow Cross - were suddenly left without a provider. They now had to survive on their own.

Benjy and Patrick did what they could by selling matches and firewood on the streets, but their meager incomes weren’t nearly enough to keep the family going. Starving and out of options, the O’Neils were ultimately forced to turn to the Parochial Board, the last refuge for the destitute.

And Benjy, the oldest, had a cough.

The family went before the Board to plead their case.

The family stands silently right in front of them as Board members speak openly about their faults, judging their situation, picking apart their choices, and wondering aloud whether they’re worthy of help at all. Finally, the Board decides to extend some relief and sends the family to Barnhill Poorhouse.

The cast then break into the first song of the play, called “Brand New Day” - a song of celebration for what seems like the O’Neil’s salvation. But this elation fades quickly when they learn the family are to be split up upon entering the establishment; there were separate quarters for men and boys, and women and girls. Benjy is given a tartan scarf to show which quadrangle he belongs in.

But the grim reality soon hits: this is no refuge. At Barnhill, the poor were berated and stripped of their dignity. Residents were forced to work long, punishing hours. Their suffering is seen not as something to be eased—but as something deserved, proof of some deeper moral weakness.

This part of the play has a solid foundation in fact. Barnhill Poorhouse was a real institution in Glasgow. It was called the Glasgow Barony Parish Poorhouse at Barnhill, and it was opened in 1853. It remained open until 1948, when the National Health Service was introduced. Barnhill’s name was then changed to Forest Hall Home & Hospital and housed a mostly vagrant population, though it still retained a section for old folks. The facility was eventually closed in stages from 1978 until 1983.

The ghostly Benjy returns to the present and cannot contain his contempt. Barnhill was supposed to be the “jewel in the crown of Glasgow's treatment of the poor,” he sneers to the audience.

Then we once again go back to his past, where we see Benjy and his brother Patrick punished by the Barnhill teacher, Mr. Carter, for trivial reasons. He takes the stick to them, and eventually Patrick is sent away.

We then visit Benjy’s mother and sister, where they work their fingers until they bleed picking oakum. This was a process of pulling old rope apart into loose fibers, which would then be used to make a preparation which sealed gaps and made them water-tight. The women sing a song called, “Circles,” which is a critique of the workhouse system’s dehumanizing treatment of the poor and disadvantaged.

Meanwhile, Benjy grows sicker and sicker. Despite being told they’d treat his cough, he’s continuously ignored, mistreated and worked too hard. His body just can’t take it anymore. Lying alone in his cot one evening, he dies from tuberculosis.

But his spirit cannot be contained. He rises from his deathbed as a ghost, which scares his fellow inmates into scurrying away. He then gets to his feet and begins to sing a song of hope called “Love Is Strong”.

It is this song you’ll hear David singing in the clip below:

We’ll talk more about this clip later on. For now, let’s get back to the story.

After the song, Benjy begins to climb back into his cot. He pauses and stares at it for a moment, then says, “I was given a deid man's bed, and no sooner was I put in it, then I was deid.”

Benjy’s body is inspected by the poorhouse nurse and the matron, who can hardly be bothered about his fate. They cover his body with a sheet and fetch his mother and sister to his deathbed. His mother, stricken with grief, tells the matron she hopes her boy would come back to haunt her.

Little does she know he already has.

The audience breaks into applause, and the curtain comes down for the fifteen-minute interval.

-

When everyone is seated again and the play resumes, Benjy steps on stage and takes up a conversational tone with the audience. He’s sharing some of what he misses about being a ghost, and some of what makes it so impossibly cool.

Some of his commentary here seems remarkably prescient, doesn’t it?

Once again, David seems to be staring his future self in the face!

-

We return to the play, where we find ourselves at a present day care center.

Benjy remains our guide throughout the play. As a ghost, he’s uniquely positioned to show us how much better the children of today are treated in care in comparison with the poorhouses of old. But he’s also able to point out how much better it could still be. He’s a kind ghost, but he’s a trickster, too, and he takes a certain amount of glee by “haunting” the teens in care he watches in the present day.

But then Benjy gets busted…literally. In a tribute to the then-popular film, four youngsters in full Ghostbusters garb appear and suss Benjy out, which forces him into finally revealing himself to the kids he’s been haunting.

Benjy tells the group he’s been watching over them and trying to help in his own way. He acknowledges something they all know too well—that young people in care are rarely allowed any privacy. That’s when the cast launches into the song ‘Secrets’, with its powerful refrain, “Why don’t we have any secrets?” The song echoes Benjy’s message but turns it into a bold statement of resistance—a declaration that, despite living under constant scrutiny, these young people still want—and deserve—parts of their lives to remain their own.

Benjy lets the audience know he’s about to sit in on a Children’s Panel with one of the teens in care. He says it’s a far cry from what he went through with the Parochial Board in 1870, where poor families were treated like they’d done something wrong. Now, Benjy shows how Children’s Panels of the present bring together social workers and parents to actually listen and support kids in a more open and relaxed environment.

But Benjy also points out things still aren't quite right. There's a big difference between the people in charge, who often come from more comfortable backgrounds, and the kids who who come from impoverished households or at-risk situations. Strangers still make most of the decisions. They drag the kids to meetings and dig into their lives without permission.

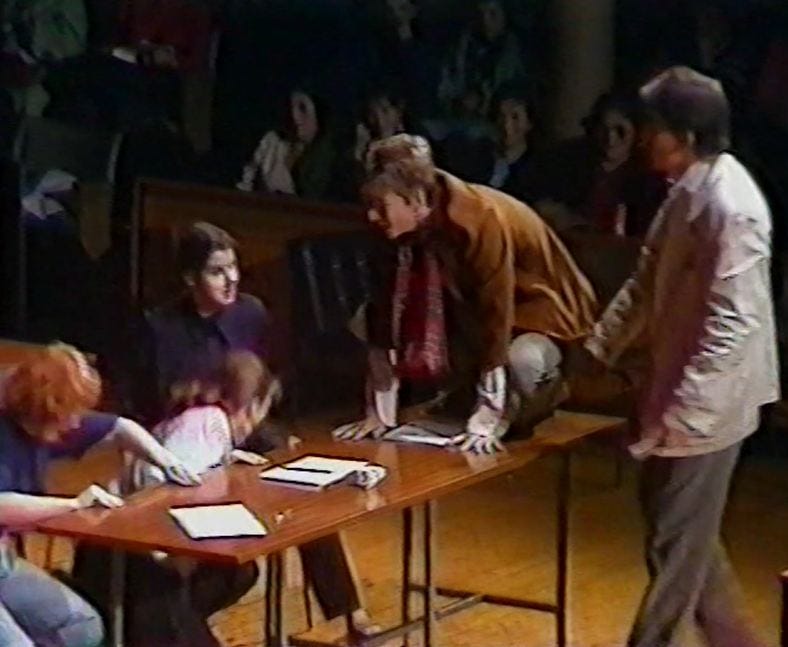

After the hearing, Benjy visits Hagburn Day Centre again. The children are working on a history project about Barnhill Poorhouse and the teacher is giving them a verbal quiz. Benjy watches silently for a while before he reveals himself to the teacher and the students, and then playfully jumps up on a table.

After everyone calms down, Benjy shares the truth about life at Barnhill and how much harder it was in his time. He reminds them how lucky they now have it. But he also says he realizes that while things have improved, there are still problems. The system often forgets to listen to the kids it’s meant to help.

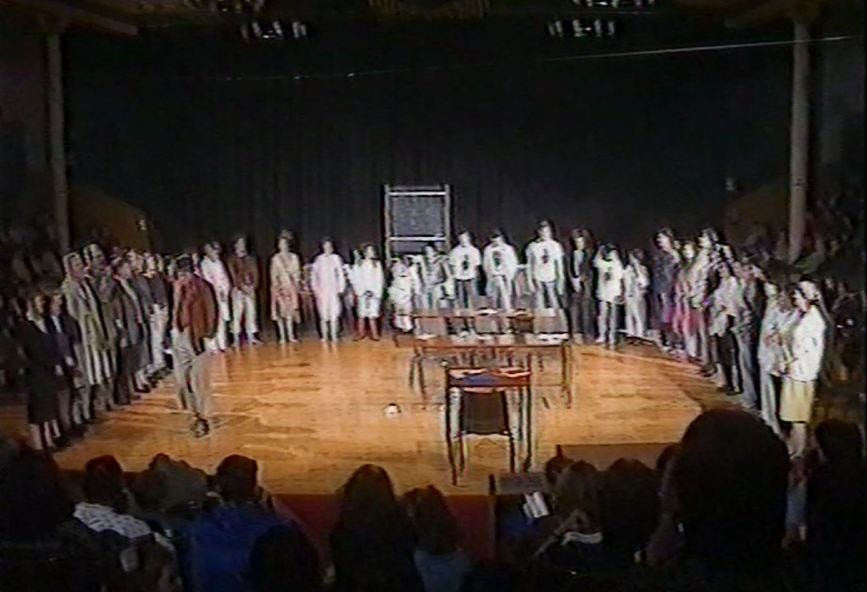

In the final scenes of the play, the entire cast comes out on stage to sing the closing song, ‘No One Knows Better.’

In the middle of the song, Benjy once again steps to the front to talk about the people who make the decisions:

“That's the trouble wi' experts, innt’it?" he asks. "They always know best. They always know what’s best for ordinary people, don’t they? I mean look at high rise blocks for young families. Look at the deserts with windows they call housing schemes. Gie a person a piece of paper frae college and suddenly he knows it all!”

Benjy’s message to the audience is clear: part of listening to the “experts” about social work means asking the actual “clients”, i.e., the kids in care.

As the play draws to a close, the entire cast appears on stage to finish singing the final song:

And that, my friends, ends my (general) blow-by-blow breakdown of the VHS recording of ‘The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil’. I hope you enjoyed reading it as much as I did writing and sharing it!

Before the curtain falls on this chapter of The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil, I hope you’ll allow me to share a few delightful little trivia gems I uncovered during my research.

To kick things off, let’s take a look at the song David sang in the clip above: 'Love Is Strong’. If you thought his voice cracked, wobbled, or fell flat here and there—you're absolutely right!

“If you listen to his solo song in the video,” Robert McAteer told me one day during our lengthy back-and-forthing about the play, “you can hear his voice croaking and quivering. Though he was on the mend at the time of filming, it was only about five days after he first became ill.”

I guess he was lucky he was able to sing at all, eh?

Secondly, when watching the play I caught an intriguing little twist in David’s live rendition of 'Love Is Strong': he didn’t sing the lyrics exactly as they appeared in the programme!

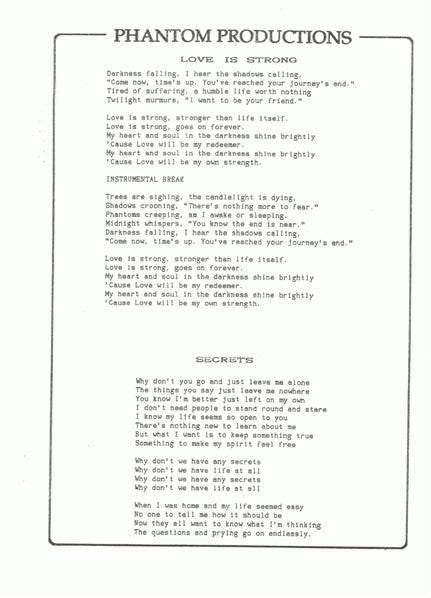

Here is the first verse as written in the programme:

When David sings this first verse live, however, it’s slightly different. His version is actually a blend of the first and third verses:

Take a listen to that first verse for yourself:

Naturally, I couldn’t help but wonder how the mix-up with the lyrics happened. Was this a last-minute revision made too late for the programme’s print run, or did David simply flub it on the night—a momentary oopsie-daisy, forever captured on tape? I asked both Tommy Crocket and Robert McAteer if they remembered, but neither of them could say for sure.

Ah, well. I guess it’ll have to be one of those quirky little mysteries lost to time. It’s what makes live theatre so unpredictable and so much fun to dig into!

Last but not least, there’s the matter of David’s shape-shifting Scottish accent.

These days his accent is still unmistakably Scottish, but I’d say it’s not quite as thick and robust as it was back in the 1990s (think Takin’ Over the Asylum from 1994). His natural speaking voice has softened somewhat over time, which I suspect has a lot to do with having spent most of his adult life living in England.

Of course, when a role calls for it—like in his recent turn as Macbeth, or as Scrooge McDuck—David can still deliver that full-bodied Scottish brogue with ease. After all, anyone familiar with his work knows he can dial it up at will.

But is that what he was doing in The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil? Throughout the play he’s unmistakably and gloriously Scottish. Was that roughly how he spoke at the time, with just a little bit of emphasis for the stage? Or maybe it was a deliberate choice, and he was directed to lean into a thicker accent for the role of ghostly Benjy. If so, I haven’t any confirmation of that. And if it was a conscious choice...why? Everyone there was already pretty darned Scottish. Why amp up the Scottish accent in a play set in Scotland, performed in Scotland, alongside a Scottish cast, for a Scottish audience?

Unlike the lyric slip-up—where there’s probably a clear explanation—the question of whether David’s accent has actually changed is much harder to pin down. There’s plenty of room for interpretation, and even more space for people to argue based on personal opinion. I’d be interested to hear yours in the comment section!

-

And that’s it for this time! I really hope you enjoyed finding out more about The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil than you thought you’d ever know. Goodness knows I loved sharing it with you!

Though to be fair…

when I saw this BBC Scotland interview from September 2023, I had to laugh to myself. After I learned the play existed back in 2017 and got busy doing all my subsequent digging, documenting, and obsessing…someone else just casually confirmed the play existed on video? Yup! There David was, doing press for Good Omens, and the interviewer just casually drops that she’d seen him in the play as a kid because her mum was in the cast and also had a VHS copy—which she’d had transferred to DVD!

Ah, well. At least the screen didn’t fade to black while bold text read: “Plot twist! You were scooped in 2023 by someone’s mum and a dusty videotape!”

I mean, yeah. She scooped me. Ha! But I’m not bitter. I’ve still been able to share background, drama, the entire plot, audio and video clips, and a few blurry screenshots. And ya know what? There’s a whole lot more to come!

NEXT TIME…what happens to The Ghost of Benjy O’Neil - and its cast - now that its four debut performances were such a resounding success? Glasgow’s time to shine as the 1990 European City of Culture was right around the corner. Would Benjy become a part of that excitement?

To find out, be sure to check out my next chapter!

This was peak! A complete joy toe read your well paced story and to warch the clips! Thank you so much!

Poor darling having to sing a solo while sick, especially since the role also required him to have a fake cough in the lead up to the scene. As someone who used to get sick pretty easily and also have a flair for the dramatic, I know that trying to force a cough while already having one is a terrible idea. No wonder the strain can be heard in his voice on the 4th performance in 3 days.

If the lyrics thing truly was a slip up, it's a good thing David changed both the 2 and 4th line, so that the rhyme was preserved.

As for the accent, it does seem stronger than in the anti-smoking commercial from '87 or Dramarama, although his character in the latter is supposed to be from Edinburgh, so that might not be a good sample of what David's natural accent sounded like around the time. He'd have less incentive trying to change his accent for a Scottish anti-smoking campaign though, so based on comparison with that, I'd lean towards he was doing it intentionally and my best guess as to why would be to make Benjy stand out even more from the modern day kids, and/or make the voice of Benjy more distinctive from other characters in general, with the goal of making it easier for people who might not have a clear view of the stage to identify when Benjy is talking. This is pure speculation on my part though, and not even a particularly educated guess.